Five Star Veterinary team members Liz Alatorre, Shelby Cody, and Hillary Sims take extra precautions when moving a combative cat named Leo to the examination table.

Leo the cat was not happy.

Leo had been brought into Five Star Veterinary in Springfield because of a severe loss of balance, and he fought with fury the staff who tried to examine him. The noise that Leo produced was the textbook definition of “caterwauling.”

Meanwhile, the Five Star waiting area and the private consultation rooms were full of other clients, humans who had brought in their animals that could not be seen promptly by other local veterinary practices.

The Five Star facility, and the people and animals that frequent it, are the latest evidence of a critical veterinarian shortage in the United States.

“We’ve been busy from the start,” said Melinda Kilty, D.V.M., a partner with Five Star Veterinary. “The second that we opened we had people coming in, some from as far as Chicago.”

Five Star was opened this spring primarily to deal with the increasing number of people who could not get their pets in to be seen by their primary veterinarians. The acute shortage of veterinarians offered an opportunity, and Five Star took it.

“We have needed a referral hospital for a while and not many people have stepped up so we just decided to do it and it’s taken off,” Kilty said. “All of the veterinarians around have started embracing us and sending us a lot of their clientele.”

Erika Eigenbrod, D.V.M., is the other Five Star Veterinary partner.

“We had seen in Springfield specifically that a lot of people were unable to get into primary care veterinary offices,” Eigenbrod said. “Appointments were booked out several weeks and there seemed to be a pretty big need for a daytime urgent care veterinary hospital.”

“Traditionally primary care veterinarians do emergency care, it was just getting to the point where people and pets were not able to get in because there was such a demand to be seen,” Eigenbrod said. “I think veterinary medicine was headed in that direction, but COVID accelerated everything.”

The United States will need nearly 41,000 additional veterinarians and more than 133,000 more veterinary technicians by 2030, according to a recent Mars Veterinary Health report. With an average of 2,500 graduates becoming veterinarians each year, that leaves a shortage of 15,000 veterinarians in eight years. That could leave 75 million pets without medical care in eight years, the report concluded.

“There are just not enough bodies to take care of pets.”

While Five Star Veterinary handles overflow and emergencies during the day, the Animal Emergency Clinic has for years been the go-to Springfield veterinary facility for after-hours needs. Gary Minder, D.V.M., has done eight years of emergency veterinary clinic work, much of it at the Animal Emergency Clinic.

“In the old days, it used to be once you got past midnight it would be pretty rare for something to come in. Now it is nonstop.” Minder said. “Maybe the wait back then would be an hour or two, and now it could be six to eight hours.”

One recent night in Springfield, Minder and his veterinary technicians could be seen handling a constant stream of pet owners with sick or injured dogs and cats. They also saw their fair share of people who simply could not get into their regular veterinarian’s office for routine care.

Read Also: Discover Your Perfect Bully Breed Companion

Photo by David Blanchette.

Veterinarian Kristi McCullough and veterinary technician Kylie Badman examine a dog at Laketown Animal Hospital. McCullough is a traveling veterinarian who fills in at area practices where needed.

“There are just not enough bodies to take care of pets,” Minder said. “Most practices will leave blank maybe an hour in the morning and an hour in the afternoon but I know that those spots are always filled in the first half hour.”

That leaves locations like Five Star Veterinary and the Animal Emergency Clinic as the go-to places for people with concerns about their pets.

“We just can’t see as many pets as need to be seen, and it puts a lot of stress on the staff,” Minder said. “A lot of times things are so fast-paced that you have to decide on what to do at that moment and you always second-guess yourself because you just don’t have time.”

Minder has 33 years of experience as a veterinarian. For the past 14 years, he operated Grace Veterinary Clinic in Chatham in addition to pulling overnight shifts at the Animal Emergency Clinic. Sept. 14 was his last day at Grace, and he is moving to Florida to become a relief veterinarian, filling in where needed to ease the vet shortage in the Sunshine State.

“It’s been described as a slow tsunami. It’s not going to get better any time soon,” Minder said. “If you look at all of the craziness going on in the world and the speed at which it is happening, people are hard-wired to need to love and take care of something, and therefore pets are huge.”

“We want you to work whenever you’re available to work.”

Kristi McCullough, D.V.M., of Pawnee, has been practicing for 21 years and is currently a relief veterinarian. She travels to different practices in the area that need help, “kind of like a substitute teacher or traveling nurse.”

“I did relief work about 15 years ago and at that point, I was covering vacations, maternity leaves, spending blocks of time at practices covering those kinds of things,” McCullough said. “Now, I’ve got several practices that just say, ‘We want you to work whenever you’re available to work.’ So I’m working a day or two at several practices just trying to help take some of the load off of them.”

That load can be overwhelming, McCullough said because there just aren’t enough veterinarians around to handle it.

“I know as a practice owner we wanted to hire another veterinarian for at least a couple of years even before the pandemic,” McCullough said. “Then the pandemic just exacerbated the problem that much more.”

“Especially with practice owners, this is their business, their livelihood, and if there are no other veterinarians there to work a shift then it falls on them to do so,” McCullough said. “That absolutely could lead to burnout. They are working six, sometimes seven days a week with not a lot of time to recoup and it takes a toll.”

McCullough said that clients of the practices where she works relief are quite receptive and are simply pleased that they can get their pets in to see a vet.

“As long as they are getting good quality care, they are not picky about who is providing it,” McCullough said. “This is just a different angle of being able to help people and pets. It is pretty gratifying to know that some of these vets that are starting to feel a little bit burned out can take a breath.”

“It is tough to find people that are willing to do that.”

Nowhere is the shortage of veterinarians more acute than in practices that see large animals, such as the cattle, pigs, horses, and goats you find on many area farms. The work is physically demanding, the hours are long, and veterinarians often get called out in the middle of the night. The pay rate is also lower because most large animal practices are in rural communities that can’t afford to pay the salaries that many vet school graduates can find in urban, pet-based practices.

“We have been trying to hire a vet for three years. We finally have somebody on their way, they signed a contract and have a start date coming up soon and that’s exciting for us,” said Jennifer Schirding, D.V.M., who divides her time between the Petersburg Veterinary Clinic and the Cornerstone Animal Hospital in Pleasant Plains. “We have three full-time doctors that share the load between the two clinics but it’s been really busy, really tough to keep schedules.”

Photo by David Blanchette

Veterinarian Gary Minder and technician Alissa Bixby checked over a small dog that was brought to the Animal Emergency Clinic.

Schirding didn’t grow up on a farm but got interested in large animal veterinary work because of a love for the outdoors and science. She is concerned that fewer younger people are following in her footsteps.

“There aren’t as many farm kids, people don’t grow up around it and just aren’t interested in it,” Schirding said. “We are available to our clients 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It is tough to find people that are willing to do that. And it is very physically demanding, especially with large animals.

“I still love what I do, it’s just challenging sometimes,” Schirding said. “As far as more vet school graduates, yeah, we need more, bring them on!”

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has the only veterinary school in Illinois. The university is seeking approval from the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education to increase the number that can be accepted into the school to 150 students, up from the current number of 130.

“We have a lack of supply to meet the demand. I have students just starting the third of their four years who are getting job offers from practices that are willing to give signing bonuses,” said Dr. Lawrence Firkins, the University of Illinois Veterinary School Dean. “Right now the typical veterinarian is exhausted. There is an increased demand for veterinary care of a comparable level to what people expect for themselves.”

Firkins said more than three-quarters of the students enrolled in the school’s veterinary medicine program are women, as are two-thirds of the program’s faculty, and a shift in the profession from food animal care to care for pets has attracted more female interest in the profession.

“The most challenging are the practices in rural communities that serve both large and small animals,” Firkins said. “There are areas where we can’t even get students to look at the practices. People from suburbia want to go back to suburbia.”

“We need to get young people exposed to the profession and show them ‘this is what it looks like,'” Firkins said. “During COVID when we couldn’t meet with family or people, a lot of animals in shelters got adopted. Now those animals all need veterinary care.”

“It’s not even about money, they just aren’t around.”

Sangamon County Animal Control uses veterinarians to monitor the health of the animals housed at the animal shelter in Springfield. Lately, that’s been tough for the Sangamon County Health Department, which oversees the Animal Control program.

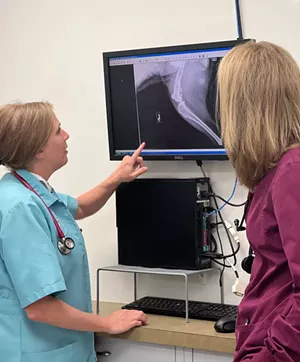

Photo courtesy of Kristi McCullough.

Veterinarians Christina Holbrook and Kristi McCullough consult over a patient X-ray.

“We had fewer hours from vets who were able to come and help us in our shelter to check on the animals. We had times where we only had a few hours a week of vet care,” said Gail O’Neill, Sangamon County Public Health Department director. “We looked at trying to partner with the Animal Protective League or anybody else to try to get a veterinarian here.”

“It’s not even about money, they just aren’t around,” O’Neill said. “And when they are, they are extremely expensive.”

The Public Health Department saw the problem coming and has taken several steps to address the veterinarian shortage, O’Neill said. The department created the position of animal care manager six months ago and filled the job by hiring Andrew Lehman, who has more than 20 years of experience working in a veterinarian’s office. Improvements were also made to the animal shelter to make it easier to monitor and care for the animals.

Two private-practice veterinarians, including Animal Control medical care consultant Kate Luthin, D.V.M., are able to work several hours per week and are available by phone to consult with the animal care manager, O’Neill said. The Sangamon County Board appropriated a $50,000 emergency care fund so animals at the shelter can be taken to see a veterinarian if needed.

However, it remains a struggle to find veterinarians willing to help the Animal Control program.

“We have found that the veterinarians aren’t all in private practice anymore,” O’Neill said. “Some of them are associated with corporate operations where they can’t compete, so they can’t do a lunch hour at the local animal clinic or shelter.”

“The animals that come to our shelter aren’t like the pets we take to our vets,” O’Neill said. “We often don’t know the environment the animals are coming from, if they’re sick or they’ve been abused. You just don’t know what you are getting, and most of the time they haven’t been well cared for.”

“We are humans too.”

The United States has the highest average per capita spending on veterinary services, averaging $162 for every citizen in the country, according to the job-search company Zippia.

Veterinarians earned an average of $99,250 per year in 2020, according to the website pawsomeadvice. More than 126,000 veterinarians are currently practicing in the U.S.

But the website also notes that the average age of veterinarians is 44.5 years, meaning a wave of retirements is just ahead, and vets are 2.8 times more likely to commit suicide than the general U.S. population.

The job is in demand but very demanding for both veterinarians and veterinary technicians.

As he prepares to leave for Florida to become a relief veterinarian, the Animal Emergency Clinic’s Dr. Minder keeps reminding his fellow workers that they must learn to deal with the stress of the occupation.

“To survive in this you’d better learn to put up a wall. We are humans too, we all have our pets, and we know what it feels like to not be able to get them in,” Minder said. “You bond with these people and come to love their pets and what ends up happening is, even if you did your best and diagnosed everything, they can still die. And it hurts. And you have to learn how to deal with that or it will eat you up.”

Photo by David Blanchette.

Five Star Veterinary team member Liz Alatorre carries a client’s dog to the holding area of the daytime urgent care clinic.

Minder added that pet owners can do their part while the veterinarian shortage continues.

“You can’t control what pet gets diabetes or cancer, but pet owners should do their best to try and minimize hazards,” Minder said. “Baby-proof things at home so dogs can’t eat them, remove things that can cause injury when pets are running freely.”

“Keep up with the wellness of your pets and be more proactive,” Minder said. “We all do it. We think, ‘Oh, he vomited once, maybe he’ll stop.’ Then two days later when he keeps vomiting we are scrambling, trying to get into a veterinarian who’s already overbooked.”

Today’s successful veterinary practices must proactively deal with the inherent stress of the occupation. Five Star Veterinary’s Dr. Kilty said their clinic, which handles overflow from other practices, realizes it’s about the humans as much as the animals.

“We are a little different in that we put our staff first, so this whole hospital is built towards them,” Kilty said. “In turn, they invest in their education a lot more and value themselves more highly, so they work a lot harder.”

Kilty moved from Connecticut to take advantage of the opportunities in Illinois. As she and her fellow team members finally got Leo the cat calmed down enough to examine him and draw blood, Kilty said she was happy to be working at Five Star.

“There are referral hospitals like ours everywhere in Connecticut but it costs a lot of money to get in,” Kilty said. “Here the vet experience is very personable, you get to know the people, and it’s pretty affordable. I like doing veterinary medicine here rather than back in Connecticut.”

Source by www.illinoistimes.com