CASTELLAMMARE DI STABIA, Italy—It was a warm summer afternoon and Assunta “Pupetta” Maresca was tapping her manicured jet-black fingernails on a white marble tabletop that was stained with what looked like red wine or blood. We were sitting in the kitchen of her fluorescent-lit apartment in a coastal town of questionable character south of Naples where she was born into a crime family in 1935, and where she died December 29, 2021. The heavy wooden shutters were closed to keep out the heat, and a ceiling lamp swayed in the breeze created by a flimsy plastic fan perched on the counter.

It was months before the COVID pandemic changed the world, and Pupetta’s biggest health fear was suffering a stroke, despite doing nothing to prevent it. A pack of menthol cigarettes in a gilded case sat neatly next to an ornate ashtray and matching lighter in the center of the table. A bedazzled vape pen on what looked like a rosary hung on her chest like a necklace. She puffed on it between cigarettes and blew smoke directly into my face. More than once she told me she shouldn’t smoke. “These will kill me,” she said between puffs. “I should stop.”

The crepey skin on the backs of her small hands was too smooth for a woman in her eighties and looked as if it had been surgically stretched around her swollen joints. Her age spots had been bleached and looked like fading bruises, as if someone had clutched her hand too hard. She briefly put her cigarette in the ashtray and picked up a strand of her crimson-dyed hair that had fallen onto the table and stretched it between her fingers, lifting her pinkies ever so slightly before brushing it off to the tile floor for her maid to eventually sweep up.

It was impossible to look at Pupetta’s hands without imagining them wrapped around the silver Smith & Wesson .38 pistol she once fired in the defining moment of her life. More than sixty years before I sat with her, she used that gun to take down the man who ordered the fatal hit on her husband. Surely her husband’s rival was dead after her first blasts knocked him to the ground. But she still grabbed her thirteen-year-old brother Ciro’s revolver and sent another round of bullets—twenty-nine in all—in the direction of the bleeding corpse. The killing took place outside a busy coffee bar in Naples in broad daylight. She was eighteen years old and six months pregnant at the time.

Pupetta claimed she still kept the pistol in the nightstand next to her bed. I once asked her if I could see it, but she insisted that she would only take it out to use it. I never asked again. Of the many things I grew to admire most about the woman nicknamed Lady Camorra was her dry sense of humor. She was a cunning liar and a cold-blooded killer, but if you could look beyond that, she was genuinely delightful.

The first time I sat in Pupetta’s kitchen—after stalking her at her usual coffee bar and vegetable market until she agreed to grant an interview without charging me for it—she offered me bitter espresso served in a chipped demitasse cup, clearly saving the fine china for better company. I stared into the dark, steaming liquid, hesitant to take a sip out of concern that she could have slipped something into it. In a brief bout of egotism, I envisioned that perhaps I could be a last-hurrah killing. No one even knew where I was, and for someone with her connections to the underworld it would be reasonably easy to get rid of my body. Covering crime and murder and death—essentially trafficking in tragedy—for the many years I’ve been in Italy has jaded my perception of my own mortality. Over the years, I have evolved from thinking that nothing bad will ever happen to me to expecting it. I see the worst first, as I am often reminded by friends and family. I am generally a voice of doom. In my defense, the paranoia was bolstered by the fact that Pupetta was not drinking any of the espresso herself. Too much caffeine in the afternoon made her nervous, she answered when I asked if she was joining me. I drank it in one gulp, as is the custom in Italy. She watched me closely, enjoying my fear—or at least that’s how I choose to remember it. Every time I saw her after that, she also drank coffee with me no matter what time of day.

As we spoke that first afternoon, a radio station played Neapolitan folk songs peppered with advertisements for private home-security services. When the news bulletin came on, she touched her ear to signal me to be quiet so she could listen to see if anyone she knows had been caught up in something unseemly.

Pupetta was wearing a dark purple tank top that pushed her enormous soft breasts together to create wrinkly, freckled cleavage over which the vape pen perilously dangled, at times threatening to fall inside. She was sitting on a squeaky wooden chair on a faded Thulian pink floral pillow that made her seem much taller than she is. Every time she fidgeted, the chair let out a tired groan, prompting the old French bulldog sleeping at her feet to growl in his sleep.

Everything that was not covered in plastic in Pupetta’s adjacent living room was instead draped with crocheted lace doilies. Pretty hand-painted blue-and-yellow plates from Sicily hung on the walls and elegantly framed pictures of her twins at various stages of their lives were lined up on a polished chest of drawers against the dining room wall. There were no pictures of her first son, Pasqualino, to whom she gave birth in prison while serving a sentence for murder and who mysteriously disappeared when he was eighteen years old.

Outside the window, the beaches of Pupetta’s hometown are littered with fuel canisters and discarded fishing gear washed in from the polluted Mediterranean Sea. Signs warn swimmers to avoid the water, but there are at least half a dozen elderly men digging for clams out there on any day of the year. In the winter, they wear thigh-high waders and heavy jackets. In the summer, they’re in brightly colored Speedos and flip-flops. The seafront town has one of the clearest views anywhere of the full breadth of Mount Vesuvius, the volcano that destroyed the original town of nearby Stabiae during its infamous AD 79 eruption.

Castellammare di Stabia sprung from those ashes and is synonymous with moral decay—so much so that in 2015 a local priest performed an exorcism by helicopter, symbolically spraying out gallons of holy water high above the 65,000 inhabitants to make sure he didn’t miss a single sinful soul. Crime didn’t stop, though the aerial blessing did miraculously make the town’s calcium-clogged fountains spring back to life, or so the legend goes. The Neapolitan Camorra’s criminal roots run too deep here for a clerical cleansing, and Pupetta is emblematic of all that is wrong about this crime-ridden backwater.

Pupetta’s father was not a top boss, but a notable criminal gang leader whose territory included Castellammare di Stabia and the neighboring hamlets that dot the winding roads between the tourist haven of Sorrento, overlooking the stunning Amalfi Coast to the south and the gritty backstreets of Naples to the north. He was a known and respected criminal among his peers, specializing in contraband cigarettes, which was a lucrative enterprise in postwar Italy.

The Maresca family clansmen were known as Lampetielli, or lightning strikes, named so for the deadly efficiency of their signature switchblades, used in equal parts to threaten and kill. As happens to be the case, Pupetta’s first trouble with the law came in primary school, when she knifed the daughter of another local criminal. The charges were dropped when the victim suddenly refused to testify. When I asked her about it, she called the whole incident “blown up” and merely a childhood spat, despite the fact that she knew how to wield a weapon before she had her first menstrual period.

Pupetta’s four brothers tried to protect her honor and keep her away from the untoward advances of suitors who approached with something other than honorable intentions. It proved a daunting task. From a very young age, Pupetta knew how to exploit her beauty for whatever she wanted, and she continued to try to do so long after it had faded.

At its rawest, most nubile, she used her attractiveness, confirmed by a local pageant title, to lure emerging Camorra boss Pasquale “Pasqualone” Simonetti. Pasqualone ’e Nola—Big Pasquale as everyone called him—was a mountain of a man with wiry black hair and a round chin that melted into his thick stubbled neck. At more than six feet tall, he towered over his “little doll,” from which the nickname Pupetta derives. Italian often use the suffix -one to describe things that are larger than normal. Christmas dinner is not a cena but a cenone, and a big kiss is not a bacio but a bacione. Pasqualone fit the customary use perfectly.

He was a classic Camorra underboss—wealthy, well dressed, and ruthless. He commanded respect through the usual tenets of the criminal underworld: extortion, coercion, and casual murder. Before Pupetta came into his life, Pasqualone was called the presidente dei prezzi, “president of prices.” He lorded over the Camorra’s vegetable and greengrocery racket in the heart of the bountiful Neapolitan farmland, which at the time produced about a quarter of a million dollars in annual profits (around U.S. $2.2 million in today’s money), from tomatoes, zucchini, potatoes, peaches, and lemons.

In 1952, Pasqualone was sentenced to eight years in prison for the attempted murder of Alfredo Maisto, an associate-turned-rival who had started edging into his cigarette territory.

As soon as Pasqualone was behind bars, another close associate, Antonio Esposito, known as Totonno ’e Pomigliano, or Big Tony, took over his share of the vegetable price racket, promising Pasqualone a cut while he was in the can. At first, he funneled some of the profits to Pasqualone behind bars, but within a few months he was keeping everything for himself.

In 1954, just two years into his eight-year sentence, Pasqualone was suddenly released from prison after new evidence emerged in the attempted murder charge—or, more likely, after a judge was threatened or paid off. Naturally, he wanted his old turf back and soon he picked up right where he’d left off. Just as predictably, Big Tony had no intention of giving up the new territory. But Pasqualone was too preoccupied with other matters to notice the tension brewing.

If two years in jail had taught Pasqualone anything, it was that he didn’t want to be alone. He watched how his fellow inmates’ wives and lovers enriched their idle time, and he wanted someone to dote on him as well. He had met Pupetta shortly before he went into prison. She caught his eye after she won a local beauty pageant and he decided she would be his bride.

He was as equally impressed by her beauty as her criminal pedigree from the Lampetielli clan’s line of work. Once in prison, he encouraged her love letters with lofty responses and promises of a life together. Within days of his release, Pasqualone started courting her seriously, and Pupetta’s brothers—who had previously prohibited her from dating any other clansmen—stepped out of the way and quickly approved of her new suitor, knowing that someone of Pasqualone’s ranking would boost their own.

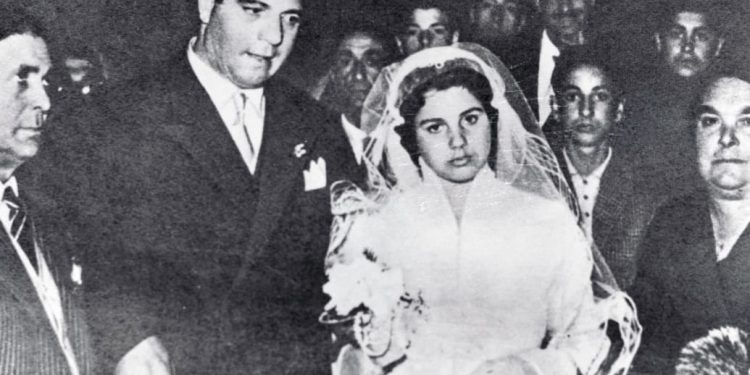

Pupetta and Pasqualone were married on April 27, 1955, when she was just 17 years old. More than five hundred guests filled the church for the lavish Catholic wedding, including the influential dons of the Camorra clans who showered them with jewelry and envelopes stuffed with cash. Even those with whom Pasqualone had sparred over territory, like Big Tony, and a gun-for-hire named Gaetano Orlando, whose nickname was Tanino ’e Bastimento, attended to celebrate the union of two important criminal lineages. Everything was perfect, and though their life together would never be easy, it seemed destined for blissful longevity.

514980814

At the wedding of Pupeta Maresca and Pasquale “Pasqualone” Simonetti in Naples, Italy.

Bettmann

They set about making their new home, and Pupetta said she was determined after they got married that they would leave their life of crime and do something less risky. It is questionable whether that was ever possible, and of course in retrospect it is an easy claim to make. The reality is that it would have been too hard for them to leave that life. They had no employable skills, and criminal associations and reputations that would have made any potential employer nervous. And anyway, those born into such strong criminal families rarely leave that world alive. Just months after their future together seemed sealed, on a blistering humid day in mid-July, Pasqualone lay slowly bleeding to death from gunshots to the gut following an attack carried out in Naples’ steamy central market square during the busiest time of the morning. Pasqualone was at the market to collect protection money and distribute favors among the farmers under his control. He was shot while peeling an orange handed to him by one of them, which has caused some speculation that the offer of fruit was meant as a distraction and that the shooter did not act alone.

The square, lined with basilicas that include the ornate Santa Croce e Purgatorio, where elderly women still gather every day to pray for the souls of the dead who are stuck in purgatory, was packed when the shots were fired. But the only person who ever said they saw who pulled the trigger was Pasqualone himself.

A newly pregnant Pupetta was called to the emergency room and wept at his bedside for the nearly twelve hours he lingered until he died at dawn, sending her shattered dreams to his grave with him. Between his last breaths, Pasqualone told his young wife that the shooter was Gaetano Orlando, one of their wedding attendees. He also told her Orlando was sent by Big Tony, the rival who tried to cut him out of the vegetable-market racket while he was in prison.

A few days later, Pupetta buried her beloved, whom she referred to as her Prince Charming or Principe Azzurro until the day she died. She vowed upon his grave to avenge his death, even though it was unheard of at the time for a woman to make such a claim. “Those days were long and lonely,” she told me as she paged through the faded black-and-white photographs and newspaper society-page clippings plastered in her crumbling wedding album. “I was at a point where I could just fade away or make things right. I decided I had no choice but to make things right.”

Pupetta always blamed the police, saying they left her no choice but to take justice into her own hands. Even as an 18-year-old pregnant mob widow and clansman’s daughter, she’d had enough faith in the rule of law to believe the authorities would help her. But the clear lack of urgency by the police to hold someone accountable for her husband’s broad-daylight murder forced her to rely on her own methods over the state’s.

Pupetta said she told police that Big Tony ordered the hit on Pasqualone and that Orlando pulled the trigger. Orlando was eventually arrested and sent to prison, but prosecutors chose not to act on Big Tony’s role. “I gave his name to the police but they said they needed proof to arrest him,” she told me, though the police records from that time tell a slightly different story in that she gave a different name than Big Tony’s, clearly hoping they would arrest someone else as a warning that he would be next. “What they really meant was that they didn’t have the balls to get involved or that they owed him protection.”

Big Tony was keenly aware that the death of such an up-and-coming guappo like Pasqualone would be avenged. So he threatened Pupetta, playing manipulative games like leaving messages in places where he knew she would be to catch her off guard. It was his attempt to scare her—warning her that if she did anything, she and her unborn baby would disappear without a trace. Still, Big Tony knew well the rules under which they all lived, especially the most important: Leaving a murder such as Pasqualone’s unavenged was out of the question. But his biggest mistake was underestimating the young widow and discounting the possibility that she would carry out the act of revenge herself.

Pupetta remembered vividly the day of Pasqualone’s funeral. It was that day when she decided that she would be no fool or vehicle to elevate Big Tony’s position in the ranks. “I took Pasqualone’s gun from his nightstand and carried it with me from the day I buried him until the day I used it,” she says. She never once doubted that she could do it. As the children of a clansman, she and her brothers had all learned how to shoot a gun to defend themselves. Their father made sure of it. “He taught me to shoot and made sure that I could hit any target between the eyes,” she explained, recounting the story of her loving father teaching her to shoot in the same way someone else might recall a parent helping their child learn to play a musical instrument or swing a baseball bat. “I was a good shot from the first time I picked up a piece, and I made him proud.”

Nearly three months after Pasqualone was laid to rest, Pupetta, by then bulging in her final trimester of pregnancy, finally got to use the weapon. When I asked her to describe Pasqualone’s gun, she pretended to point the imaginary firearm vaguely toward my forehead. “It was a petite gun,” she said, pulling the air trigger as she made a clicking sound with her tongue. “It was the kind you carry in a little clutch purse like you’d take out to a nice dinner.”

On the day that would set the course of Pupetta’s life, she had asked her thirteen-year-old brother, Ciro, to come with her to the cemetery to lay flowers on Pasqualone’s tomb, as remains the custom for new widows in this part of Italy for a year after a husband’s death. Their driver, Nicola Vistocco, was also going to stop by the market square where Pasqualone was killed so Pupetta could pick up some produce, which was given to her for free.

On the way to the market, she spotted Big Tony coming out of a busy coffee bar on the Corso Novara, not far from the square where her husband was shot. She asked Nicola to pull her Fiat over, and he slouched low behind the steering wheel while Pupetta waited. Once Big Tony was walking down the Corso Novara, she asked Nicola to drive up to him. Nicola stopped the car and Pupetta jumped out and started shooting, a gunfight ensued and Pupetta, protected by the car, easily escaped any harm. The driver didn’t see a thing, he told police. He and Ciro were both later tried and convicted for acting as accessories to murder.

Pupetta initially claimed that he had tried to open the car door and she pulled her gun only in self-defense. She claims not to remember pelting Big Tony with what police claim were 29 bullets, insisting that it was just “one or two shots” from the back of the car delivered out of fear. But the evidence used to convict her—including gruesome autopsy photos— showed she used Pasqualone’s Smith & Wesson with precision, and then used the revolver carried by her little brother to make sure he was properly dead. Five of the bullets went straight into her husband’s assassin’s skull. Some reports suggest that four guns were used, which would help explain the astonishing number of bullets. It would also imply greater Camorra involvement and an organized vendetta. When I asked, Pupetta brushed that off and insisted that the reports don’t take into account that the area where the murder took place was already littered with shell casings and the walls were scarred from previous gun battles.

The two siblings fled the scene, leaving the crimson chrysanthemums meant for Pasqualone’s grave in the back seat. When Pupetta died, I bought chrysanthemums in the same color as she described to place on the family tomb where she was interred, though police wouldn’t allow me to do so, as any nonfamily celebration of her life was prohibited.

After a few weeks in hiding, Pupetta was ratted out and arrested for Big Tony’s murder. It seemed especially telling to her that she was so easily brought to justice after all she went through to try to get the police to find anyone responsible for her husband’s murder. The fact that they did not turn the same blind eye to Big Tony’s killing convinced her that either his clan controlled the local investigators or that he was an informant.

During her murder trial, she showed no remorse at all, instead telling the court that she would “do it again” if she had the chance. It was her duty to avenge her husband’s death in the absence of the law, she said, screaming during one hearing, “I killed for love!” before collapsing in the courtroom. Local newspapers covered the trial like it was a social event. Headlines screamed about Pupetta’s many outbursts in court, often paying the same attention to detail in describing how the youthful defendant dressed and batted her long eyelashes as newspapers normally paid to starlets of her generation like Sophia Loren, a contemporary who also grew up in the area.

The prosecutor in the case said that by acting to avenge her husband’s death—essentially playing judge, jury, and executioner for a crime never tried in court—she was participating in what they called an “episode of gang warfare” and argued for a life sentence. Her lawyer argued first that it was a crime of self-defense, an argument that Pupetta had promptly undermined on the very first day she testified with her outburst about killing for love. He then changed tack to try to defend the case as a diletto per amore, or an “honor crime,” which covered a broad category of offenses that could somehow be justified by heartbreak. Crimes to defend one’s honor were so common in Italy they were even considered an extenuating circumstance in sentencing until the 1990s, when it finally became more difficult, though even today not impossible, for a cuckolded husband to kill a cheating wife or a mafioso avenging murder to get a pass.

The trial, which also included the side attraction of Pasqualone’s hit man Gaetano Orlando’s case, was open to the public, and a number of Big Tony’s associates were present in the gallery to make sure that the omertà, or code of silence that extends across all of Italy’s criminal enterprises, was properly respected. Of the 85 witnesses called, very few said they saw anything, knew anything, or would speak of anything relevant to the court’s final deliberation.

Fulfilling the vendetta served a second by-product—and one that Pupetta never could have imagined. The act lifted her to icon status among the Neapolitan criminal elite, earning her the nickname Lady Camorra and giving her incomparable stature as an original madrina—a godmother. After just one appearance in court, local Camorristi started throwing flowers onto her police van roof as it traveled between the jail and tribunal, as if she were royalty passing by in a horse-drawn carriage.

Pupetta was quickly found guilty and sentenced to 24 years in prison, which was reduced on appeal to 13 years and four months. She served less than ten years, winning a suspicious pardon in 1965 that likely grew from a deal brokered for information. She dismissed that wholeheartedly when I asked her, insisting that new evidence against Big Tony proved that she had indeed justifiably killed her husband’s assassin, and that the judge finally saw the light. Even though I had been told by an assistant to the prosecutor who helped secure her release that a deal had been cut, it made more sense not to confront her with the truth. This is a woman who has time and again shown very little respect for what Italians call the verita.

From THE GODMOTHER by Barbie Latza Nadeau, to be published on September 6, 2022 by Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Barbie Latza Nadeau.

Source by www.thedailybeast.com